And this is hardly an exhaustive list of racist threads citing or discussing the show. On 4chan, a website now nearly synonymous with the alt-right, the rabid message board /pol/ has archived 57 distinct threads with Attack on Titan in the subject line since 2016 alone. Not everyone sees Attack on Titan that way, however. Hidden in Attack on Titan’s blood and gore is a deft exploration of the legacies of violence. Meanwhile, Isayama’s erstwhile protagonist is a genocidal maniac radicalized by trauma, and all of his former friends are cooperating to thwart him. Soldiers’ deaths are meaningless far more often than they are glorious. Isayama turns the topic’s inherent potential for jingoism on its head: Though nearly the entire cast is composed of soldiers, many are cowardly and selfish. The inequality and propaganda espoused by the fascist military regime are major obstacles that the protagonists must overcome. In the internment camps, the broadly sympathetic Eldians are marked with starred armbands-an apparent reference to the yellow badges the Nazis forced Jews to wear. Most people consider Attack on Titan a work that straightforwardly condemns the effects of fascism and racism in society. Isayama’s silence just makes it easier for audiences to transpose their own ideologies onto the world has created.

Attack on titan list of titan attacks series#

As a result, the “true” political message of the series has been the subject of furious debate online. Whether by cultural osmosis or coincidence, Isayama littered his series with allusions to racial, ethnic, and historical tropes. Isayama’s intent, however, does not remove the politics from Attack on Titan. “Ultimately, I don’t think passes judgment on what is ‘right’ or ‘wrong,’” he added.

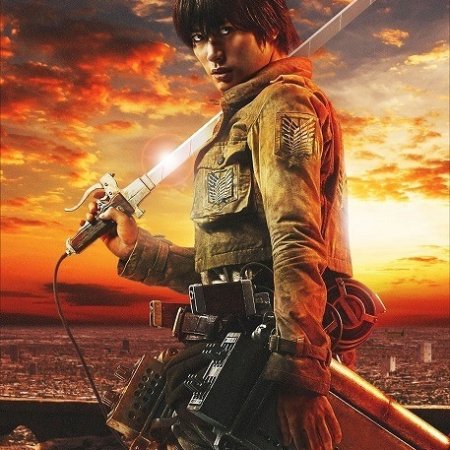

Attack on titan list of titan attacks movie#

He has stated that he admired the movie In This Corner of the World because it did not answer explicitly whether war is good or bad. He also dislikes didactic storytelling, instead preferring stories that do not provide straightforward answers to complex moral questions. He believes his concept of an unequal, walled society, with monsters outside the walls, is “universal.” He compares the walls to the mountains ringing his hometown, Oyama, which he associates with his childhood preoccupation with the idea of escape. He traces the origin of his idea of human-eating creatures to his childhood on a farm, where he was fascinated by the cruelty of animals eating other animals. When asked about what influenced Attack on Titan, Isayama references everything from video games to his frustrations with himself. By 2014, Attack on Titan was available to watch on Netflix, Hulu, and Cartoon Network, in addition to anime streaming sites like Crunchyroll and Funimation.

The property reached global popularity with the animated show helmed by Tetsuo Araki, famous for his work on the series Death Note. The difference between the alt-right and the left, of course, is in the interpretation of who is persecuted. Though its creator insists that his work’s inspirations are apolitical, he has won acclaim from liberals and the alt-right alike for his story of armed revolution by the persecuted. Hajime credits his work’s wide appeal to its simple premise: “Humanity on the verge of extinction due to the rise of man-eating giants.” Yet over the past decade, the story has moved from a simple narrative of Humans Versus Monsters into an elaborate saga. When its English-language televised adaptation debuted on Cartoon Network’s Adult Swim in 2014, the pilot drew more than 1.3 million viewers. The series has sold over 100 million copies since Bessatsu Shonen Magazine released the first issue of Attack on Titan 11 years ago. Inspired by these phantoms, Hajime, a quiet, polite man, wrote and illustrated Attack on Titan, one of the most popular manga to gain a following outside of Japan. Many wandered around aimlessly, struggled to communicate, were drunk and belligerent. He found the customers strange and often frightening. Isayama Hajime worked nights at an internet café.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)